Rup and Jadrup

BY: ACARYA DASA

Jun 10, 2016 — INDIA (SUN) —

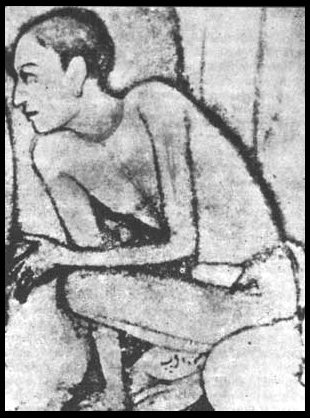

Many contemporary Vaisnavas will instantly identify the person in this image as Sri Rupa Gosvami, one of the principal disciples of Sri Krsna Caitanya, and one of the most influential theologians of the Caitanya tradition. It has been used widely in print and online publications as a painting of Sri Rupa, and has been the inspiration of many contemporary depictions of him (like this one). It was also obviously the model of the murti that has, in rather recent years, been placed on top of his tomb (samadhi) in the Radha Damodara temple in Vrindavan.

But is this really a picture of Rupa Gosvami?

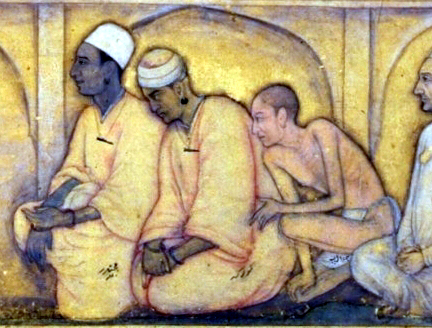

Mystics in Ecstasy, circa 1650-1655. Now held in the Victoria & Albert Museum.

The above painting is a depiction of a gathering of Sufis, in Ajmer at the tomb of Mu’in ad-Din Chishti, a Sufi saint who was instrumental in spreading Sufism in India. It was painted between 1650-1655, probably in the atelier of Dara Shikoh, son of the emperor Shahjahan. In the top of the painting, there is a row of Sufi saints some of which are identified as great Sufi masters of the past, including Mu’in ad-Din Chishti himself (centre, wearing a red cloak and holding a book), looking on while contemporary Sufis dance themselves into ecstasy in the centre of the painting. (Note also the two very European looking men in the top left corner!).

But the most interesting part is the bottom of the painting, where twelve figures are seated. They are influential Hindu saints, and are all identified in Persian. The first nine, from left to right, are: Ravidas, Pipa, Namdev, Sena, Kamal (Kabir’s son), “Aughar” (a general name for an uninitiated Nath ascetic), Kabir, Pir Muchhandar (the Panjabi name/form of Matsyendranath), and Gorakh.

And then we come to the crouched figure many might immediately identify as Rupa Gosvami. The figure is identified as Chadrup or Jadrup. After Jadrup is Lal Swami or Babalal das Vairagi, a teacher of Dara Shikhoh. Of the last figure’s name only the title “Swami” is legible; this could be Chitan Swami, Lal Swami’s guru.

Pir Muchandar, Gorakh and Jadrup.

Who is Jadrup? He was a Hindu ascetic from Ujjain, whom both Akbar and his son Jahangir liked. Akbar met him, and, according to Jahangir, always remembered the meeting fondly. Jadrup is listed (among nearly only Muslim teachers) in the Ain-i-Akbar as one of the contemporary sages who “understand the mysteries of the heart” and who “pay less attention to the external world, but in the light of their hearts have acquired vast knowledge.” Jahangir took a special liking to Jadrup, and visited him often. He is often mentioned in Jahangir’s memoirs. Below are a few passages about him from the Jahangir-nama bout the emperor’s meetings with this ascetic.

March 1616-March 1617

It has been repeatedly heard that near the town of Ujjain an ascetic sannyasinamed Jadrup Ashram had been living for several years in an out-of-the-way spot in the country far from civilisation, where he worshipped the true deity. I very much desired to meet him and had wanted to summon him and see him while I was in Agra, but in view of the trouble it would have caused him I didn’t do it. Now that we were in the vicinity, I got out of the boat and went an eight of a koson foot to visit him.

The place he had chosen for his abode was a pit dug out in the middle of a hill. The entrance was shaped like a mihrab, one ell tall and ten girihs [1 girih is about 2 inches] in width. The distance from the entrance to the hole in which he sat was two ell three girihs high from the ground to the roof. The hole that gave entrance to his sitting place was five and a half girihs tall and three and a half girihs wide. A skinny person would have great difficulty getting in. The length and width of the pit were the same. He had neither mat nor straw strewn underfoot as other dervishes do. He spends his time alone in that dark, narrow hole. In winter and cold weather, although he is absolutely naked and has no clothing except a piece of rag with which he covers himself in front and behind, he never lights a fire. As Mulla Rumi says, speaking in the idiom of dervishes: “Our clothing is the heat of the sun by day, and moonlight is our pillow and quilt by night.”

Twice a day he goes to make ablutions in the river nearby, and once a day he goes into Ujjain, enters the houses of only three Brahmins out of the seven married persons with children he has chosen and in whose asceticism and contentment he has confidence, takes in his hand like a beggar five morsels of food they have prepared for themselves, and swallows them without chewing lest he derive any enjoyment from the taste–this provided no calamity has occurred in any of the three houses, no birth has taken place, and there be no menstruating women. This is how he lives.

He desires no intercourse with people, but since he has acquired a great reputation, people go to see him. He is not devoid of learning and has studied well the science of Vedanta, which is the science of Sufism.

I held conversation with him for six gharis [i.e. 144 minutes], and he had such good things to say that he made a great impression on me. He also liked my company. When my exalted father had conquered the fortress of Asir and the province of Khandesh and was on his way back to Agra, he also paid him a visit in this place and often mentioned it with fondness.

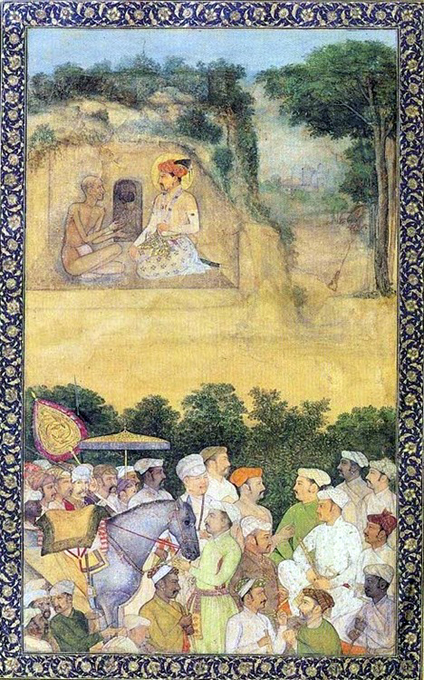

Jahangir Converses with Gosain Jadrup, from a Jahangir-nama manuscript, circa 1620.

Jahangir returns to visit him many times in the following years. Here are two more passages from his memoirs that give a little more information about Jadrup:

On Saturday the second [November 13 1618] I had a great yearning to converse with Jadrup again. After performing my noontime devotions I got in a boat to go see him. Toward the end of the day I hastened into his corner of retirement and talked with him. I heard many lofty statements about gnostic truths, and he explained the fundamentals of mysticism without obfuscation. One can really enjoy his company. He is over sixty years old. He was twenty-two years old when he severed his ties to material things and set out on the highway of renunciation, and he has been in the “garb of garblessness” for thirty-eight years now. As I was leaving he said, “How can I express my gratitude for this God-given occasion? I have occupied worshiping my deity with ease of mind and freedom from concern during the reign of such a just monarch, and never has any worry come to my doorstep.”

Later, Jadrup moves to Mathura:

March 1619-March 1620 Recently he [Jadrup] had moved from Ujjain to Mathura, one of the major temple sites of the Hindus, and worshiped the true deity on the banks of the Jumna River. Since I was anxious to talk to him, I went to see him and spent a long time alone with him without interruption. He is truly a great resource, and once can enjoy and derive much benefit from sitting with him.

Jahangir visits Jadrup. Painted by Muhammad Aslam, circa 1750-1775.

There are more passages in the Jahangir-nama about Jadrup, but all are more or less like the above. We don’t get a very clear picture of his religious background or commitment. He seems to have been a Advaitin sannyasi (as the title Asrama indicates), who studied Vedanta. The Dabistan-i Mazahib does not consider Jadrup to be a follower of Sankara (see Moosvi 2002, 16-17). He could have been a Vaisnava, as many Advaitin sannyasis were in those days, but this is a little unlikely, given that his theological views are considered by contemporary accounts to be very close to the rather monistic Sufi teachings.

In any case, the above image of Rupa circulated among devotees is based on a photocopy of the image of Jadrup in this painting–the Persian inscription (just under his left leg) is preserved in the photocopy, and the lines in the background of the “Rupa” painting correspond perfectly to the architecture and the clothing of the surrounding figures in the Mughal painting. (Note also how Jadrup is nearly always depicted in a similar pose–Mughal illuminators were great copyists and often “remixed” older paintings into their own.)

I don’t know how this picture came to be identified as Rupa Gosvami, though, and, unfortunately, I haven’t been able to trace the history of its use in contemporary Vaisnava culture.

- The Jahangirnama: Memoirs of Jahangir, Emperor of India. Translated, edited, and annotated by Wheeler M. Thackston. Washington, D.C. : Freer Gallery of Art & Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institute in association with Oxford University Press, New York, 1999.

- Chaghtai, M. Abdullah, “Emperor Jahangir’s Interviews with Gosain Jadrup and his portraits” Islamic Culture 36,2 (1962), 119-28

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda K., “Portrait of Gosāīṅ Jadrūp”, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Volume 51, Issue 03 (July 1919), pp 389-391.

- Gadon, Elinor W., “Dara Shikuh’s mystical vision of Hindu-Muslim synthesis.” In: Facets of Indian Art. A symposium held at the Victoria and Albert Museum on 26, 27 April and 1 May 1982. Eds. Robert Skelton, Andrew Topsfield, et.al. London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1986, pp. 153-157.

- Moosvi, Shireen, “The Mughal Encounter with Vedanta: Recovering the Biography of ‘Jadrup’” Social Scientist, Vol. 30, No. 7/8 (Jul. – Aug., 2002), pp. 13-23

#SunEdit

Leave a Reply