“So you need a new place, right?”

The Storefront Temple, July 1966

Mukunda: One evening a few of us were sitting and talking with the Swami, when he said,

“I was thinking of having a Love Feast with singing, dancing and eating. No one will refuse such a function. What do you think?”

No one spoke. A few nodded and made expressions of approval, but I was thinking,

“Where did he get the words Love Feast? That sounds like counterculture jargon, not our erudite Indian swami.”

I was surprised by his assimilation of American hippy vernacular.

The word “feast” sounded bacchantic to me, like something social and self-congratulatory.

I expected that it would be a party of some kind where the Swami would treat everyone to the delights of Indian cuisine and would shore up his success.

It wasn’t that I didn’t want to go; it was more that the philosophy in his books was a serious matter for me, and I wasn’t interested in what I considered to be the social aspects of his mission.

I wasn’t very gregarious or people-centered; I thought spiritual life was more or less a private affair. And I really couldn’t figure out how dancing fit into it all.

Eating, yes. Singing or chanting, sure. But dancing? That didn’t seem to go with the chanting. The Swami said that chanting was a spiritual sound and was for getting in touch with the Supreme, Krishna.

How could you dance and do that at the same time? Our chanting was always done in meditation posture, sitting on the rug, cross-legged. There didn’t seem to be any place for dancing. The only kind of dancing I could think of was ballroom-style or square dancing.

A couple of nights later at the end of the evening chanting session, he made his announcement.

“So, on Sunday afternoon we will be having a Love Feast here. You please all come.”

As he spoke I looked around the dismal loft and failed to imagine how any kind of festive atmosphere could be achieved in such a place.

Even though I wasn’t very enthusiastic, I decided to go because he was so insistent and because I wanted to be courteous. He hadn’t given us much notice, but I lived in the here and now, and longterm planning wasn’t part of my agenda.

On Sunday afternoon, several people showed up at the Swami’s loft. The lecture platform was out of sight and had been replaced by a big round wooden table that someone had dragged to the end of the lecture area. The table was covered with food of all kinds, some on trays and some in large strange pots without handles that were pocked on the outside with what appeared to be random hammer marks.

The Swami circulated around the room, smiling and talking in an animated manner with everyone. I stood to one side, unsure that I would be able to come up with any small talk.

Moving through the small groups of people, he was no longer the sage, the wise man from India; he was an affable, indefatigable host. Not used to seeing him standing up, I was struck once again by how small he looked in comparison to the other people in the room.

The smells coming from the pots were intriguing. I edged over to the table to see what the food looked like.

The pots were full of various vegetable and bean dishes: a dark brown chickpea stew, creamed spinach with pieces of milk curd, yellow rice studded with peas, and an eggplant and tomato curry with chunks of fried golden potato.

On a tray to my left were pastry fritters accompanied by a dish of rich-looking tamarind chutney. Beside it were a tray of pale brown sweets and a deep bowl of creamy dessert with strands of saffron floating in it.

Carl came up behind me, followed by his live-in girlfriend Carol. Both she and Jan had come to a few of the Swami’s programs, but neither of them was really into the philosophical or spiritual side of things. They had sat at the back of the gatherings, not nearly as moved by the Swami as me.

“It all looks pretty good, huh?” I said.

“Yeah. The Swami cooked everything himself,” Carl said.

“And I helped him,” Carol added. “I loaned him some of our pots because he doesn’t have a lot of stuff himself. It’s really amazing watching him cook. He doesn’t taste anything at all when he’s cooking because he says the food has to be offered to Krishna first. He told me that everything should be cooked with love.”

“With love?”

“That’s what he said. Like if you love your boyfriend or girlfriend or your child and you cook with care thinking about pleasing them, your cooking will be full of love. So I guess he cooks thinking about Krishna, almost like a meditation.

“He’s really focused, you know? At the end when everything was finished he said some prayers over the food. That’s the offering part. He called the food prasadam after he offered it.”

The Swami suddenly appeared next to us, handing us each a china plate. Rather than leaving it up to us to help ourselves to what we wanted, he served us each preparation. Throughout the evening, he moved energetically around the room with a pot under his left arm and a serving spoon in his right hand.

“Take, take,” he said, grinning and piling more and more portions onto our plates without waiting for us to say yes. “You’ll like it. You will.”

I cautiously tried two bites of the chickpea stew when all of sudden he was in front of me with another ladleful. “Take more!” he insisted. Nobody refused. Carl looked up and nodded his head each time, mumbling through mouthfuls of food, “OK, OK.”

“You like?” the Swami asked me.

I could only nod, chewing and swallowing. The whole event seemed to mean a great deal to the Swami, and I didn’t know why. I wasn’t sure where any of this was going to lead. What follows a Love Feast? At least there was no dancing, thank god!

The ringing of the telephone tore me out of a deep sleep. Carl’s voice was loud in my ear. “The Swami and I were just going for a little walk and we thought we’d come up and see you.”

I looked at my watch: 7:00 AM. I’d recently gotten a job in a Staten Island nightclub on the weekends and I’d been asleep for only two hours.

“Carl, you’ve got to be kidding me! I just got home and I’m sound asleep!”

“The Swami wanted to come up and see you.”

“Where are you?” I asked.

“We’re at a pay phone on the corner.”

The pay phone was fifty feet from my front door. “But we’re in bed.”

“Well, the Swami really wants to see you.”

I sat up in bed. “You’ve got to give me at least five minutes. I

have to get up.” Jan rolled over, turning toward the wall away from me and the phone.

“OK,” he said. “We’ll be there.”

I dragged myself out of bed and tried to pull myself together. Just as I was buttoning my shirt, the doorbell rang.

The downstairs door must have been open, because they were suddenly already up the two flights of stairs and at our front door. Jan slept on.

Half-dressed, I opened the front door.

“Come in, Swami,” I said. “Here. You can sit on the couch.”

The Swami sat in the middle of the couch, while Carl and I sat at either end.

“So, this is your home?” the Swami asked me.

“Yes it is, Swami. We rent it for really cheap; it’s a good place to make music.”

The Swami nodded and looked up as Jan staggered in looking sleepy in her nightgown and a bathrobe.

She rubbed her eyes and looked like she was trying very hard to focus on the unexpected guests in her living room.

“Oh, hi Swami,” she said. “I’m Jan. We haven’t met properly, but I was at your Love Feast last week.”

“Yes, I saw you there. You are Michael’s wife?” he asked. “Wife?” She glanced at me and gave a short laugh that came out sounding like a yelp. “Not exactly, no. We just live together.”

I thought I saw a flash of disapproval in the Swami’s eyes, but it quickly dissolved.

The television was still on from the day before. There was no sound, but cartoons were playing one after another. It was a black and white TV with a rainbow-tinted glass in front of the picture tube, which was supposed to give the impression of color. I didn’t even notice it was on, but the Swami did.

“This is nonsense,” he said, gesturing toward the TV.

Looking over at the animation, I said, “Oh yes, this is nonsense.” I quickly turned it off.

As we engaged in small talk, Jan brought some peeled and separated orange sections in a dish, which she offered to the Swami.

“That’s a nice touch,” I thought, smiling at her. Jan knew I was pretty into the Swami’s philosophy; she thought it was a good thing, but it was definitely my thing.

Scuzzlebrunzer, our black cat, suddenly jumped up on the Swami’s lap. I thought it quaint that he had perceived such peace in a stranger. But the Swami pushed him away. Later, when I finally visited India, I thought back to this incident and realized the vast cultural differences between Western and Eastern perceptions of animals.

In India, while most people respect animals as spiritual equals, they do not intimately associate with them. Dogs and cats, in particular, are street animals that are considered dirty and generally are not allowed to enter homes or temples.

Scuzzlebrunzer was friendly, but there was a sense that he had been overly familiar with the Swami. Later I understood this incident from the Swami’s cultural standpoint, but for now, I felt his rejection of the cat was a little out of character for a holy man.

“So how long have you been here in this loft?” Carl asked. “About one year,” I answered. “Why?”

“The Swami needs a better place to live, because Paul’s getting out of hand.”

“What do you mean?”

“He’s just getting hard to live with. You know, he swears, acts weird, disappears for hours on end. And he’s rude, loud and unpredictable. You know, he’s just weird.”

He shrugged his shoulders. “Weird to live with anyway, at least for the Swami.”

Paul had always struck me as immature and without direction. Still, he didn’t seem particularly difficult to me; a bit odd, maybe, but everyone was in some way.

“So, how can we help the Swami?” Carl asked me.

I was silent. The Swami, perhaps sensing my lack of concern, began to tell me about Paul’s unusual behavior.

“Paul left the soap on the floor of the shower,” he said. “This is dangerous. When I asked him to pick it up, he started ill-naming me.”

A bar of soap and a little bit of swearing didn’t seem like such a big deal to me.

“In India,” the Swami continued, “we have a saying: guru-maravidya. You sit opposite a guru, learn from him everything, then you kill him, move his dead body aside, and sit in his place, and then you become the guru.”

He paused. “Paul is a very dangerous man.”

As the Swami said this he looked right through me. I felt a shiver down my spine. Paul seemed utterly subservient to the Swami, almost like a slave who lacked a mind of his own.

But as the words left the Swami’s mouth, I began to think that maybe Paul’s peculiar mindless demeanor was his own problem, part of his psychological state, whatever that was, and not part of his being a follower of the Swami’s. He certainly seemed unbalanced, and if he was taking heavy doses of drugs, maybe he could be capable of violence. It occurred to me that Paul was quite possibly a dangerous man, especially for a small, elderly Indian swami.

I looked up. “So you need a new place, right?” “That’s it,” said Carl.

I felt a little guilty and very uneasy. Was the Swami asking me indirectly if he could appropriate my place, turn it into a temple and me into a Paul replacement? I wasn’t ready for that!

“People play drums here, sometimes late at night,” I said hastily. “There are always musicians hanging around here. But maybe I can help.”

Carl said, “Well, for now, the Swami can stay at my place.”

They stood up, and Scuzzlebrunzer zoomed from his perch near us to a corner of the room.

“Thank you,” the Swami said, looking me up and down.

“OK. Bye.”

“Hare Krishna,” they said quietly in unison. As they left, I realized that the Swami was carrying a small suitcase. I wondered if he had already moved out of Paul’s loft, if the suitcase contained all his belongings.

When the Swami and Carl left, I felt strangely alone. I felt I had to do something for the Swami, but not just because I told him I would. I realized suddenly that during the past few weeks I had begun to feel I was a part of his mission. He had come to America for the purpose of spreading his mission, and to do that he needed somewhere to live. All he needed was a decent apartment of some kind, preferably on the ground floor of a building in a better neighborhood.

Experience in loft-hunting had taught me that the Village Voice, a weekly newspaper, was the best resource. I browsed the “For Rent” section and then, from the nearest pay phone, called a telephone number for a storefront located at 26 Second Avenue, about a halfhour walk from the Bowery.

I got the first available appointment with a Mr. Gardiner and telephoned the Swami and Carl to meet me and Gardiner at the premises at ten o’clock the next morning.

It was already sunny and hot for a Manhattan morning in late June. I rode my bike up the Bowery, turned right on Houston and then left onto Second Avenue. I wheeled to number twenty-six and chained my bike to a No Parking sign. I was early. The ride over had taken only ten minutes, so I checked out the place while I waited for the others to arrive.

It had obviously been a store; the whole front was glass–a large glass window and a door with a single glass pane. The name painted at the top of the glass windows was Matchless Gifts.

In the distance, a short, slim, bouncy man who looked to be about forty-five, with close-cropped silvery hair, was approaching. He wore a short-sleeved yellow sports shirt, blue denim pegged pants and white cut-down tennis shoes. He looked up and down the buildings, jangling a big ring of keys, and checking me out as he neared me. Gardiner, I guessed. He was early too.

“Hi,” I said, when he stopped at number twenty-six, “My name’s Michael. I talked with you on the phone yesterday.”

We shook hands.

“Right. Paul Gardiner,” he said in a business-like voice. “So what’s up?”

“Well, the storefront’s not for me. It’s for an Indian swami who wants to lecture here three nights a week. He’s a writer, and he wants to have some yoga classes here. He’s a pretty respected scholar; he gave some of his books to the Prime Minister of India.

“He should be here any minute. My friend Carl Yeargens is coming over with him. Carl graduated from Princeton in philosophy. He’s been working with the Swami for several weeks and … Actually, that looks like them now, see, down the street?”

“Oh yeah. I see them.” “Yeah. So can we have a look at the place when they get here?”

“That’s what I brought the keys for.”

“So, yeah, I think he’ll want to have the classes Monday, Wednesday and Friday nights around seven.”

“Sounds OK. What’ll he be doing?”

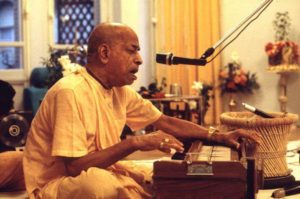

“Well, the classes usually start out with some chanting, then he lectures, people ask questions and then there’s some chanting again.”

“And what do you do?”

“Well, I’m just trying to help the Swami out. I’m a musician, but I’m learning Sanskrit and reading some of his books and learning a lot. About Indian philosophy, I mean.”

“I see.”

“Oh, here’s the Swami now. Swami, this is Mr. Gardiner. Mr. Gardiner, this is the Swami, and this is Carl Yeargens.”

They all shook hands. Carl was carrying a set of the Swami’s books.

“Your friend here’s been telling me about you,” Gardiner said, squinting and looking at the Swami. “Come on in. I’ll show you the place.”

Gardiner selected one of his numerous keys and unlocked the front door. It was a rectangular-shaped room, about eighty feet by twenty-five feet. It was bare, but reasonably clean.

A few long cylindrical fluorescent lights were twisted into white flanges that projected from a ceiling about twelve feet above the floor. The white ceiling was made of painted metal sheets, some bulging.

A large white pewter basin stuck out from the left wall at the back end of the store next to a back door. There were bars over the two back windows, which looked into a little courtyard.

“Well, this is it,” Gardiner said, motioning us to sit down on the small ledge that ran along the store’s front windows.

“How much is the rent?” I asked.

“A hundred a month.”

The Swami said, “Mr. Michael and Mr. Carl are members of our society, and they pay a subscription of twenty-one dollars a month.”

“That’s not true,” I thought.

I wondered why the Swami said this. I wasn’t a member of anything, and I certainly hadn’t given any money to join. The only money I’d parted with was the fifteen dollars for the books.

“So, I’d like you also to be a member of our society.”

He held out his three hardcover books to Gardiner. The agent smiled and took them.

“Thanks,” he said, starting to page through them.

“Please take these books. You can be a member. It’s twenty-one dollars a month, and we can pay you seventy-nine dollars a month rent. You won’t have to pay anything now.”

I began to see that the Swami was striking a deal with Gardiner, and that his claiming we were already members was a part of this. I remembered him telling me that he had been a businessman back in India.

“It looks like these books were a lot of work,” Gardiner said, looking genuinely pleased. “OK. Thank you. By the way, I also have an apartment in this building for rent.”

The three of us looked at each other, surprised. “How much is it?” I asked.

“You can have it for eighty-five dollars a month.” “Where is it?” asked Carl.

“It’s just a flight up, in the back. I’ll have to paint it if you want it.”

“Can we see it?” asked the Swami.

“Sure. We can look right now if you want.”

We followed him to the back of the store, as he flicked through his keys, looking for the right one to open the door. Unlocking it, he led us through a darkened hallway until we found ourselves in the little cement courtyard that could be seen from the store’s back windows.

It had a small camellia bush and a scanty birch tree in the middle. On the other side of the courtyard was a door that opened onto a stairway. We headed up its dim flight of stairs.

The apartment was a little old looking, but it was airy and bright. We walked around, inspecting the two rooms, the kitchen and the bathroom. Carl and I thumped on the walls, looked outside, checked out the steam radiators, flicked on the dead light switches and flushed the toilet.

I counted the number of electrical outlets. It seemed to be in reasonably good condition.

“What color will you paint it?’ I asked.

“White.”

“Eighty-five dollars including utilities?”

“No, they’re separate.”

Looking official and scratching his head, Carl said, “Maybe we can go back down to the store.” We went back down and sat on the ledge.

“I think we should do it. Get the store and the apartment,” Carl said decisively.

“That’s one hundred and sixty-four dollars a month,” I said to Carl.

“Between us and the others, we can do it. I’m sure,” Carl said, nodding his head confidently.

The Swami looked at Carl and me, poker-faced, then at Gardiner.

“You’ll have to give me a week to paint the apartment.” Gardiner smiled and added, “You can have ’em both with no deposit.”

“Great,” Carl said. “We’ll take them both.”

I unlocked my bike, and the three of us walked back to the Bowery.

“I can stay at Dr. Mishra’s for the week,” the Swami said. “He is a friend I stayed with for some time when I first came to New York. He won’t mind.”

“That’s a good idea,” Carl said.

“Mr. Michael, you can have the electricity turned on in the new store. Tell them it is for non-profit and they will not charge for deposit.”

“OK,” I said, wondering how “they” would react.

The next day I sat before a fat gray-suited bureaucrat at his desk in the Con Edison building.

“Um, I’d like to have the electricity turned on at 26 Second

Avenue and at apartment 114 at the same address.”

“How much is the rent per month in the apartment?”

“Eighty-five dollars.”

“OK. You’ll just need to pay a deposit of eighty-five dollars to us to get the electricity put on there.”

“The thing is, the place is going to be used for a non-profit organization. I thought non-profit organizations didn’t have to pay the deposit.”

“Do you have an already existing account?”

“No.”

“Do you have a guarantor or corporation papers?”

“No, but …”

“Then you’ll have to pay the deposit the same as everybody else, buddy.”

“Just as I expected,” I thought.

I headed back to Carl’s place, hoping to catch the Swami before he left for Dr. Mishra’s. I knocked and Carl let me in.

“Is the Swami still here?”

“Yep, he’s not leaving until tomorrow. Just go through,” he said, pointing to the living room.

The Swami looked up as I entered.

“I went to the electricity company, Swami,” I said. “What did they say?” he asked.

“That I’d have to pay, despite it being a non-profit organization.”

“Then?”

“I just thought, ‘OK. I’ll have to pay.’”

He seemed disappointed and annoyed. There was a distinct glimmer of dissatisfaction in his expression.

The next day, the Swami went to the Con Edison office himself and had the deposit requirement waived.

I was amazed he did this, as well as dismayed that he had to go, that I hadn’t managed to complete the thing he’d ask me to do.

Moving day. It was a warm and sticky Manhattan afternoon when the small crew of the Swami’s friends gathered to transport his belongings from Paul’s loft to the new storefront.

The move to Second Avenue resembled a safari. The expedition snaked along the Bowery, avoiding drunks lying on the sidewalk, everyone carrying something.

The seventy-year-old Swami carried two suitcases, one in each hand, as we trudged the mile-long walk to Second Avenue.

I couldn’t imagine how he was managing to carry them; it was so hot, and after his heart attacks on the way to America, this kind of exertion couldn’t have been good for him.

I was struggling with my own burden, a Roberts seven-inch reel-to-reel tape recorder. One of the regulars at the Swami’s evening programs had begun to use the heavy machine to record the lectures in the Bowery.

I carried it on my right shoulder but had to switch it back to the left shoulder and then back again several times. My arm and shoulder were sore for days afterward.

When we finally arrived at the storefront, Carl rummaged through his pocket for the key to the front door.

The rest of us, sweating and tired, rested our loads on the sidewalk and leaned on parking meters and the store window, trying to catch our breath.

Carl held the door open for the Swami. Picking up his two suitcases, he stepped into the bare, musty storefront and looked around.

The rest of us followed him in, relieved to be out of the heat. Some kicked off their shoes and sat against the walls; others found seats on the window ledge.

I put the tape recorder in the corner so it wouldn’t get damaged or kicked, and headed back home, satisfied that I’d done my part in helping the Swami to find his place and move his stuff.

Soon after moving into the storefront, the Swami decided to incorporate his fledgling movement.

“We will call it the International Society for Krishna Consciousness. ISKCON for short,” he said one day.

“Why don’t you call it the International Society for God Consciousness?” someone suggested.

“No,” the Swami said. “Krishna Consciousness.”

A lawyer named Steven Goldsmith oversaw the proceedings. As part of the process, the Swami drew up a document, which he entitled “Seven Purposes of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness.”

These purposes included:

- To systematically propagate spiritual knowledge to society at large and to educate all peoples in the techniques of spiritual life in order to check the imbalance of values in life and to achieve real unity and peace in the world.

- To propagate a consciousness of Krishna, as it is revealed in the Bhagavad-gita and Srimad-Bhagavatam.

- To bring the members of the Society together with each other and nearer to Krishna, the prime entity, thus to develop the idea within the members, and humanity at large, that each soul is part and parcel of the quality of Godhead (Krishna).

- To teach and encourage the sankirtan movement, congregational chanting of the holy name of God as revealed in the teachings of Lord Shri Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.

- To erect for the members and for society at large, a holy place of transcendental pastimes, dedicated to the Personality of Krishna.

- To bring the members closer together for the purpose of teaching a simpler and more natural way of life.

- With a view towards achieving the aforementioned purposes, to publish and distribute periodicals, magazines, books and other writings.

The Swami asked Jan and me if we would act as signatories of this document that would establish his movement as a legal entity. In our early twenties, we were almost the oldest people frequenting the Swami’s chanting evenings, so it made sense to us that he would ask us over the teenagers and less-responsible visitors who drifted in and out of the scene.

We agreed to his proposal, even though the legality of it all seemed a bit excessive given that the “movement” consisted of nothing more than a handful of alternatives and a rented storefront.

—Mukunda

[VedaBase 22. Biographies and Glorification of Śrīla Prabhupāda / Miracle on 2nd Avenue – Mukunda Goswami

Post view 531 times

Leave a Reply